Editor’s note: This CNN series is or was sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over the subject matter, reporting and frequency of articles and videos within the sponsorship, in accordance with our policies.

CNN

—

On the northern edge of the Rub al-Khali, secrets are buried in the sand.

The vast desert of 650,000 square kilometers on the Arabian Peninsula is known as ‘The Empty Quarter’. And to most, apart from the waves of ocher dunes, it looks empty.

But not for artificial intelligence.

Researchers from Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi have developed a high-tech solution for searching for potential archaeological sites in large, arid areas.

Traditionally, archaeologists use ground surveys to locate potential sites of interest, but this can be time-consuming and difficult in rugged terrains such as the desert. In recent years, remote sensing using optical satellite images from places like Google Earth has become popular for looking for unusual features over large areas – but in the desert, sand and dust storms often obscure the ground in these images, while dune patterns can make it difficult to detect potential locations.

“We needed something to guide us and focus our research,” says Diana Francis, an atmospheric scientist and one of the project’s principal investigators.

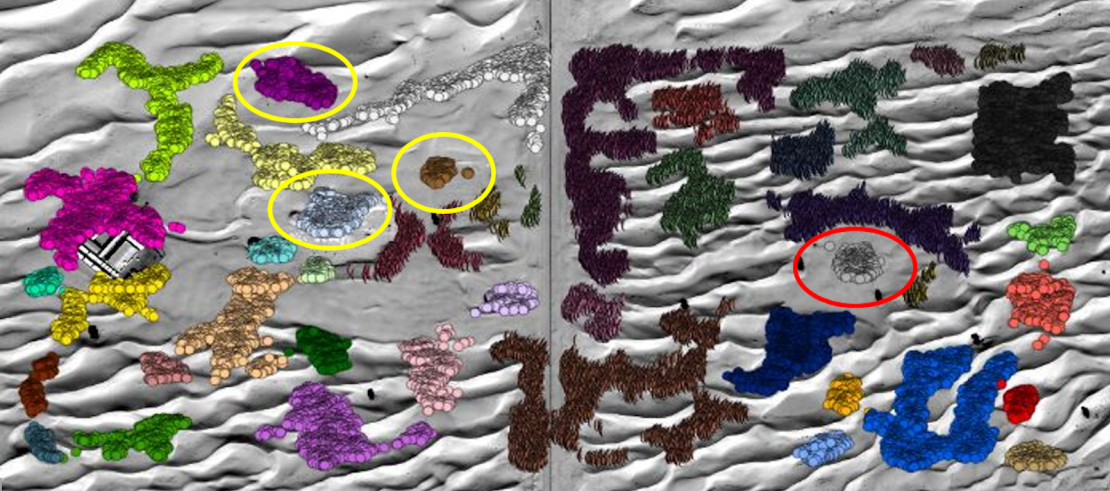

The team created a machine learning algorithm to analyze images collected by synthetic aperture radar (SAR), a satellite imaging technique that uses radio waves to detect objects hidden beneath surfaces, including vegetation, sand, soil and ice.

Neither technology is new: SAR images have been used since the 1980s and machine learning is gaining ground in archaeology. But using the two together is a new application, Francis says, and as far as she knows, a first in archaeology.

She trained the algorithm using data from a site already known to archaeologists: Saruq Al-Hadid, a settlement with evidence of 5,000 years of activity that is still being uncovered in the desert outside Dubai.

“Once it was trained, it gave us an indication of other potential areas (nearby) that still haven’t been excavated,” Francis said.

She adds that the technology is accurate to within 50 centimeters and can create 3D models of the expected structure, giving archaeologists a better idea of what is buried beneath.

Working with Dubai Culture, the government organization that manages the site, Francis and her team conducted a ground survey using ground-penetrating radar, which “replicated what the satellite measured from space,” she says.

Now Dubai Culture plans to excavate the newly identified areas – and Francis hopes the technique can uncover more buried archaeological treasures in the future.

The use of SAR images is not common in archeology due to its cost and complexity.

But using it to identify buried sites is “very exciting,” says Amy Hatton, a doctoral candidate at the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology who is researching deep learning models to detect archaeological structures in northwestern Saudi Arabia .

Hatton notes that by using SAR imagery, which circumvents the problem of light scattering by dust particles, Francis and her team have solved technical details that make remote sensing in desert areas difficult.

Khalifa University is not alone in using artificial intelligence to detect potential sites.

Amina Jambajantsan, another PhD student at the Max Planck Institute, uses machine learning to speed up the “tedious work” of searching through high-resolution drone and satellite images for potential locations of interest. Her project, which focuses on medieval cemeteries in Mongolia – a country spanning over 1.56 million square kilometers, almost the size of Alaska – has uncovered thousands of potential sites that Jambajantsan says she and her team could never have found on site.

Jambajantsan says that while the cost and computational demands of SAR imagery may be a barrier to use for many researchers, the method is valuable for desert areas where other technologies struggle – and that she would consider it for the Gobi Desert in South -Mongolia, where its “normal optical images” do not yield any results.

Machine learning is finding more and more applications in archaeology, although not all researchers are enthusiastic about it.

“There are two different belief systems,” says Hugh Thomas, a lecturer in archeology at the University of Sydney and co-director of the AlUla and Khaybar prehistoric excavation project in Saudi Arabia. On the one hand, people are pursuing technological solutions such as AI to identify locations; on the other, those who believe you need a “trained archaeological eye” to identify structures, he explains.

While technology could help identify and monitor archaeological sites – especially those threatened by land-use change, climate change and looting – Thomas is wary of over-relying on it.

“The way I would like to use this kind of technology is in areas where there may be no or a very low probability of archaeological sites, allowing researchers to focus more on other areas where we expect more to be found,” says Thomas.

The real test – and hopefully validation – of the technology will come next month when excavations begin at the Saruq Al Hadid complex, of which only an estimated 10% has been uncovered over an area of 6.2 square kilometers. area, according to Dubai Culture.

If archaeologists find the structures the algorithm predicted, Dubai Culture plans to use the technology to excavate more sites.

Francis and her team published a paper on their findings last year, and they continue to train the machine learning algorithm to improve its accuracy before expanding its use.

“The idea is to export (the technology) to other areas, especially Saudi Arabia, Egypt and perhaps the deserts of Africa,” she says.

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Amina Jambajantsan’s name